Technological advancements across all eras are arguably influenced by a single human need: the need for speed. Centuries worth of research and development represent our inclination to make everything faster—instant, even. Along our quest to hasten everything – meaning, production, and subsequent consumption – we actively developed 3D printing technology. Despite its success in streamlining the manufacture of a wide range of products, it also manifested substantial backlash in terms of Intellectual Property. As the adage goes, immense production power does not come without extensive legal responsibility. This article explores the historical backdrop of 3D printing. It then highlights the present conditions of the technology with regards to copyrights, trademarks, patents, and design laws. We then explore the legislative implications of the technology in Intellectual Property and vice versa and whether you can patent a 3D printed product.

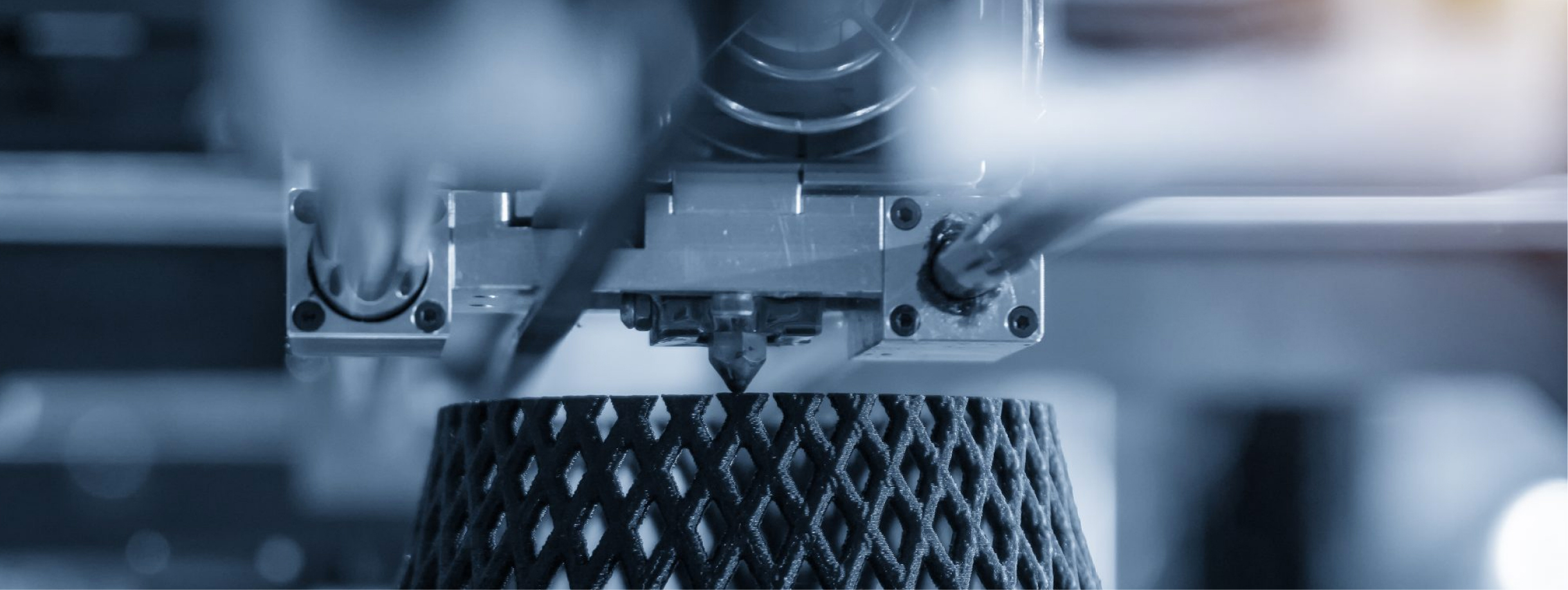

Expert Insight: In the span of the merely a decade, 3D printing technology emerged from its predecessor Rapid Prototyping (RP). The latter fabricates a scale model of the design which in turn goes through another process referred to as additive manufacturing – a term most commonly understood as 3D printing. With rapid developments, three-dimensional printing became in itself a standalone manufacturing system. It became known as Rapid Manufacturing (RM), Digital Manufacturing (DM), or Direct Digital Manufacturing (DDM), given its remarkable speed.

In 2017, it was identified by the European Union (EU) as a driver for the inevitable industrial revolution. Indeed, it facilitated many previously impossible, if not labour-intensive, feats in the field of engineering, medicine, and even the arts, among other fields.

3D printing, in a manner of speaking, is among the cogs of the manufacturing wheel as a whole. Hence, it is necessary that there be other prerequisite technologies leading to the actual physical printing. And while this might not present considerable difficulties at a glance, the compartmentalisation of data processes raises pertinent questions—especially regarding Intellectual Property.

Without surprise, many malicious entities hitched a ride on the faster production platform of 3D printing technology. Counterfeiters quickly populated online communities as our connection speeds increased significantly. The same principle of opportunistic trade applies to 3D printing tech. The internet sped up distribution, 3D printers sped up illicit production.

Copyright & CADs

Many sources contend that Computer-Aided Design (CAD) – the digital design file created through AutoCAD as a requisite for 3D reproduction – may be protectible under copyright law. The argument originates from the subsistence of copyrights for other similar technologies such as software and digital prototypes. However, some court rulings indicate the opposite. With these highly polarised stands on the issue, the consensus is clear: Copyrights for CADs are as intricate as the designs in the CAD file itself; therefore, each case warrants a case-to-case review.

The legal and industry perspectives remain unclear as to the digital file’s qualification for Intellectual Property protection. And while there have been examples of successful cases, these are mostly decided on technical grounds, such as flaws in non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and non-compete agreements. Obtaining a solid victory on a data-based copyright dispute requires expert execution of written documents in as early as the first negotiation process.

Expert Insight: Copyrights cover the expression of an idea; and data is – as of now – not considered an expression, but rather an artificially manufactured information. While qualified when labeled as “literary work,” there are other rigorous considerations to answer before official recognition as copyrighted work. When unsure about whether your CAD is copyrightable, it is best to seek legal counsel to ascertain whether your file represents artistic expression above functionality.

Intellectual Property & Design Data

Whilst data in itself do not qualify for copyrights protection, aggregate data – that is, the collection of raw data polished for 3D printing, and categorized according to function – may prove eligible for Intellectual Property protection. After all, the aggregation of information embodies its design data.

The protectability of designs as a database presents a two-pronged approach. The first is by asserting “intellectual creation” on grounds of arrangement and selection of component data, thereby enabling copyright protection. The other involves sui generis. The latter declares that a database is “in a class by itself” and therefore merits special considerations. The latter also requires proof of “substantial investment,” which, in many cases, could only work with a significant amount of time spent on the development of the object of contention.

Expert Insight: Both protective legal measures require proving the uniqueness of the data or the aggregated data in question. Furthermore, there are other limiting factors when pursuing this legal action. First of which is the protection coverage. It applies only to the “collection” and not the individual components per se. Additionally, the importance of compilation and systematic arrangement should be of demonstrable value. Otherwise, the “intellectual creation of database” and sui generis recourse would fail. It is always best to consult a dedicated Intellectual Property firm.

Printing Paths for Patents

With its formidable scope of protection, mostly utilised as fundamental components to other inventions, patents prove attractive to the 3D printing industry. CAD developers may lodge their interest to patent their design data, provided that the factor that separates them from similar trade is contained within the raw file. However, several important questions arise when patenting enters the conversation.

For instance, consider a patented component technology. If, through the same machinery, a resulting product or information is generated, the scope of the original patent becomes open for debate. Many experts challenge the extendibility of the parent patent to its resultants. Regardless of how seemingly a modern-world concern it may be, this issue has been vexing experts for quite a while. The same discussion floated around – more accurately, is still floating around – in as early as the first doubts regarding the patentability of AI-produced objects.

On the other hand, suppose that the action seeks to directly patent design data. Since we are essentially entering a hypothetical legal ground, patentability of data as an “aggregate collection” is still up for discussions. And having only a handful of relevant cases denies firm ground for jurisprudence to establish a firm stance.

In theory, design data could be patented when described as a “product” of a patented process. Bear in mind that patenting design data as “product” is different from copyrighting aggregate data. Albeit hypothetically possible, history of practice indicates the courts’ disapproval of extending patent rights beyond the original scope, as evidenced by Hunde-Gentest case.

Expert Insight: In light of the abovementioned cases, major jurisdictions consider extension of patents to its resultants contingent on two requirements: first, its repeatability for the same explicitly defined purpose; and, its general patentability excluding physical limitations.

3D Mark

Perhaps trademarks are the most comprehensive Intellectual Property protection available for both CAD and design data. The only overriding consideration to qualify is its inclusion in the course of trade. Stated precisely, design data meet the criteria for trademark protection if previously registered elements such as words, images, or the like, appear within the raw design. These aspects could potentially constitute a three-dimensional trademark, among other kinds of marks.

The Law in Three Dimensions

Ground-breaking as it is, 3D printing also poses threats not only to established brands, but likewise to our collective consciousness at large. Granted that illegal reproduction – at an unprecedented rate – is the primary pitfall to this astounding innovation, this barely scratches the surface of cascading consequences.

Inundating the market with substandard products would dissuade the public from trusting every brand—including the emerging ones; not quite in the economic scene yet, but summarily impeded by consumer distrust caused neither by their enterprise nor the corporate giants’ actions.

The dilemma is further complicated considering the relative invisibility of 3D-printed counterfeit producers. We see the products; we spot the flaws of these fake items at a glance; but we do not know of the manufacturers. Hence, the powerful frustration unintentionally spilling over and generalising the market as a whole.

The aforementioned issues – physical detriment and psychosocial implications – constitute the reasons why active policing is an absolute necessity.

However, balancing enforcement activities and preserving civil rights is an extremely thin line to tread. For instance, in theory, everybody – even in their homes – should have the right to print 3D models of anything their imaginations can muster. And it is allowed in certain parts of the world through “Private Use” or other similar provisions. Nevertheless, reselling, mass reproduction, or unlicensed distribution of “home printed” designs mark the end of the “Private Use” liberty and signify participation to illegal sales. Such demarcation between the private and public spheres easily singles out infringers just by mere association, or lack thereof, with the original brand.

Fair and square. Or so it seems. Just the process of identifying the source of 3D-printed materials could be obstructed by stringent privacy laws. If eventually located, litigation on grounds of Intellectual Property breach would have taxpayers spend their money on a relatively unexplored proceeding. Of course, new issues would never solve itself just by idly passing time. There is always a need to begin somewhere. And beginnings, if we pay attention to most history classes, always come with virtually absurd costs.

3D Printing Technology, and Laws on Intellectual Property

In retrospect, polishing the laws beforehand would facilitate effective policing. And this could very well be the best course of action. For one, it would answer pertinent legal, political, industrial, academic, and other questions. Moreover, having the representatives communicate their sector-specific concerns would provide a comfortable elbow room for much-needed adjustments. In this manner, the law directly guides the use of 3D printers.

Moving forward, active vigilance from the private sector – including civilians and business owners – would prove effective in deterring the proliferation of cheap but substandard 3D-printed items.

Proactive alertness for infringing entities could be construed as internalised manifestations of our community values. Particularly towards societal wellbeing and integrity of laws on Intellectual Property. In a manner of speaking, the negative aspects of 3D printing are, at the very least, contributory factors to shaping Intellectual Property. It necessitates the laws’ adaptation to the changing platforms of criminal activities. Even the community is actively involved—as evidenced by our pre-emptive stance in quelling the issue once and for all.

Nonetheless, inasmuch as 3D printing influences the practice of Intellectual Property, the latter also guides the evolution of this printing technology. With legal provisions delimiting the scope of 3D printing, the line between what can and cannot be reproduced is becoming clearer by the minute, albeit still far from crystal clear.

The 3D Fine Print

Powered by the innovations in our printing technology, we were able to accelerate production whilst minimising the cost in terms of time, labour, and capital. However, similar to all things harbouring immense potentials, even the 3D printer could prove detrimental when used unlawfully.

Having rigorous check-and-balance measures as stipulated in Intellectual Property laws aided in answering some pertinent questions regarding ownership of rights to manufacture and reproduce. The laws also provide a rather large space for the private sector to print their designs assuming it is for personal use. Perhaps the line between private and commercial use is the most valuable delineation extrapolated from Intellectual Property laws.

However, obliquely clarifying just two issues still leaves plenty to go around. Intricate questions on the specifics—inter alia, transferability of patents, copywriting written computer programs, trademarks for unquantifiable matters such as the algorithms behind processes—most likely depend on future court rulings across the globe.

On the one hand, it might seem defeatist – the notion of having nothing else to do besides waiting for bigwigs to hand a decision. And it is, at a certain level. But looking at the larger picture, there are plenty of more unexplored possibilities. And with said opportunities, we could actually have a hand.

Outside the Print

In this era, merely having the capital to purchase a 3D printer and its relevant software is not the only requisite to using the technology. As awareness of Intellectual Property rises among the general public, a solid knowledge of these rights proves equally important as the machine itself.

Hence, using 3D printers in commercial enterprises brings with it a plethora of best practices as well as laws to keep in mind. Understanding the “Fine Print” of 3D printing is just a preparatory step for this venture. Taking your ideas “outside the print” and into business reality is a different story altogether.

As mentioned, every now and again in this article, having expert legal counsel is the safest way to approach the 3D printing market. Every nook and cranny of Intellectual Property has, on one form or another, applications in 3D printing technology.

If you are considering turning your ideas to business reality, and if you particularly wish to course your goals by way of three-dimensional printing, our team of attorneys and expert professionals can help you. No need to worry, this is a complimentary service to help budding businesses.